Marcel Robert's view is a darkened room in a rest home:

Life with chronic illness ME

2 Nov, 2019 7:44pm 10 minutes to read

Originally published as a Premium article in the NZ Herald and reused with permission

Marcel Robert now lives in a quiet, darkened room in a rest home. Photo / Supplied

Marcel Robert lives in a rest home. He is 31 years old. Natalie Akoorie finds out what it's like to be unable to live life because of an illness and why funding for research is so important.

In a darkened room at Oxford Court Lifecare in Dunedin, a man who should be in the prime of his life is wasting away.

Marcel Robert is bedbound, unable to care for himself, barely able to hold a conversation above a whisper.

He's been living like this, solely reliant on caregivers to survive, for 18 months and there's no hope of improvement anytime soon.

Robert has myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

The debilitating condition, which affects at least 20,000 New Zealanders, causes extreme exhaustion, a post-exertional malaise - usually after a sufferer has used too much energy, sending them spiralling into a "crash" they sometimes cannot recover from.

It is typically triggered by a viral infection, such as the flu, that the body never recovers from.

In Robert's case he was struck down with glandular fever as a 14-year-old.

The previously active, sport-loving teenager missed school for months and before he could fully recover he came down with the same symptoms again.

Slowly, eventually he recovered enough to attend university but by age 20 he began waking up feeling "completely drained".

"Halfway through the year I developed a virus that I couldn't get rid of and that was when my health really took a sharp decline," Robert tells the Herald on Sunday through messages exchanged via an ME forum, because he is too sick to be interviewed.

"After the virus seemed gone I still had a lot of muscle and joint pain, constant nausea, dizziness, severe brain fog, fatigue, fevers, light sensitivity, swollen lymph nodes and a worsening of symptoms after exertion."

Marcel Robert was a happy and healthy young boy, despite losing his mum when he was 4-years-old to breast cancer. Photo / Supplied

Ron Robert says his son had been a healthy, happy boy up until the glandular fever in June 2003.

He played soccer, hockey, indoor cricket, golf and even won the cross country at school. He had plenty of friends and a loving father and sister.

His mother died of breast cancer when he was 4.

When he became sick at university with suspected swine flu, the ME symptoms flared again.

Constantly out of energy and susceptible to viruses, he dropped out of study and tried to get better.

Ron, a former school-principal-turned-real-estate-agent, took his son to ME expert Dr Ros Vallings in Auckland, who diagnosed the young man with traits of ME in early 2011.

Robert tried to maintain an independence, moving to other cities and even following a girlfriend to Sweden in 2015, but the illness eventually forced him back to Dunedin.

Ron bought his son a house and initially he managed living on his own but when Work and Income required him to work, he could only manage a few weeks before collapsing with exhaustion.

"Following medical advice I paid for meals to be delivered and home help as Southern Health refused to believe he had a physical illness, saying they didn't recognise ME," Ron says.

As his son grew sicker, he watched on helpless, and says apart from Vallings, other doctors did not believe he had a physical illness.

"They said or implied he was psychotic. The fact that he'd been an active sports player and successful student was irrelevant to their assumption he was 'putting it on'."

Robert became isolated as friends moved on.

Then he was advised to try the Gupta programme, a brain-retraining plan with which users claim to have been cured of ME.

"It made him believe his first thoughts were imaginary and to train him to think differently," Ron says.

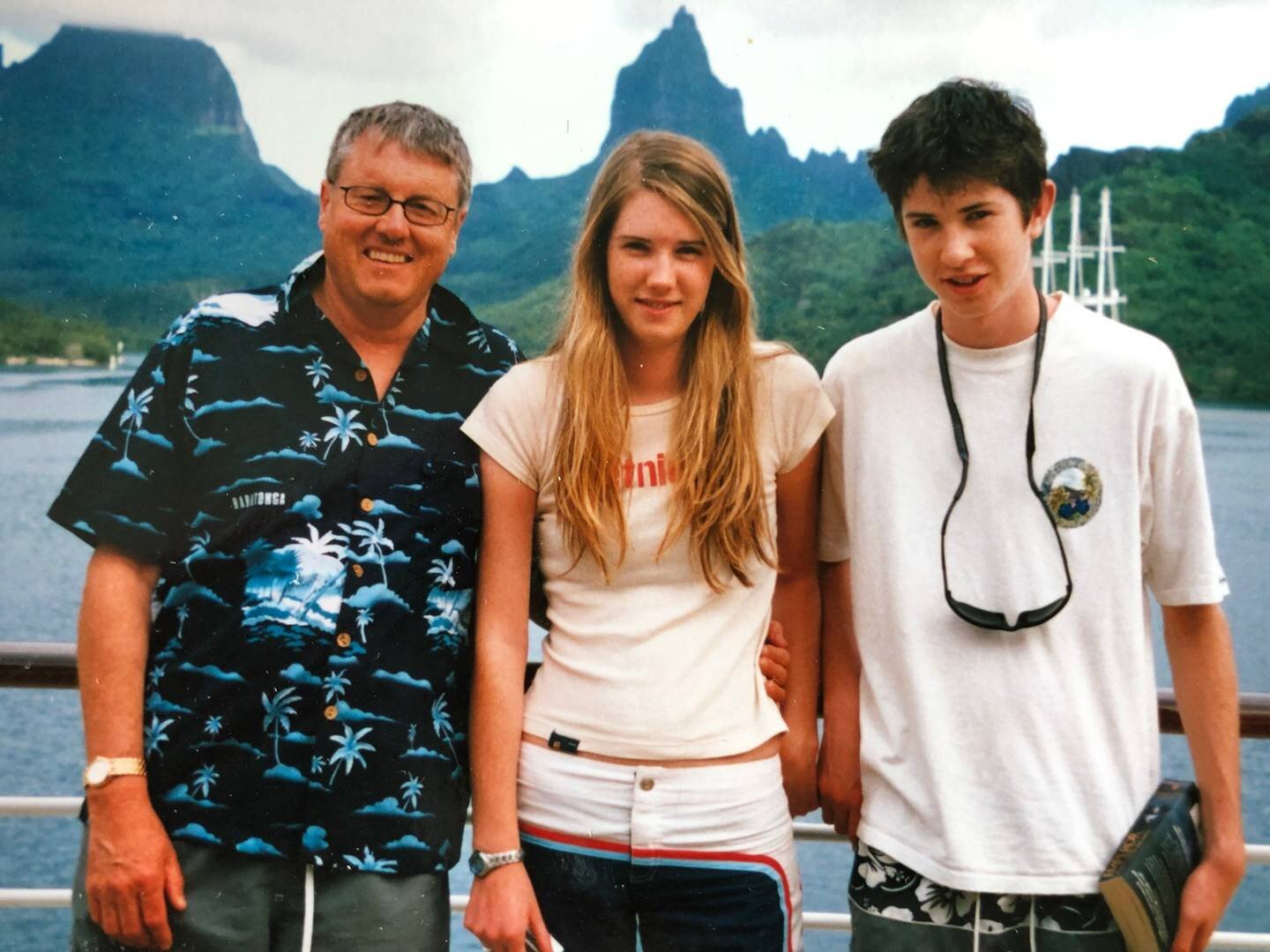

Marcel Robert with his father Ron and sister Hollie when he was younger. Marcel was struck down with glandular fever when he was 14. Photo / Supplied

It didn't work. In fact Robert grew sicker.

"Being abandoned by friends, disbelieved by doctors regarding his physical illness and doctor referrals to psychiatrists drove Marcel into a mindset that he must be mentally sick," his father says.

"Depression on top of his physical illness worsened his situation. He was accordingly sent to a mental hospital and prescribed lots of addictive anti-depressants."

Robert's stint in Wakari Hospital was short-lived. He signed himself out after two weeks.

"Marcel realised he wasn't mentally abnormal and what a relief that was. For years he had been shunned and shunted," Ron says.

"By early 2018 he couldn't move without falling so I bought him an electric wheelchair."

In March last year Robert developed shingles and was moved into temporary care at Woodhaugh Rest Home and Hospital.

"I've lived in one [a rest home] permanently since May 2018," he says.

"I don't see myself being able to move out any time soon as my ME has gotten worse over time."

Later in 2018 Robert moved to Oxford Court Lifecare, where he has lived since.

"I'm 30 and live in an aged-care facility," he says. "I'm completely bedbound, unable to leave my room.

"I'm in constant pain in my gut and muscles. Constant nausea, dizziness, brain fog, severe fatigue, fevers, burning eyes that are too sore to focus.

"I can't enjoy a view, or look at my niece. It's been years since I've had a proper conversation.

"I'm missing out on life, all the big things; kids, a career, good friendship. And all the little things that make life worth it."

Sleep doesn't come easy for Robert. An eye mask is necessary to dim light and watching television, his last distraction from reality, is becoming difficult.

But he is grateful for the compassion shown by his caregivers.

"They do a lot of little things for me here that I can no longer do myself. Things like providing meals, helping me wash daily and shower weekly, cleaning my room, washing my clothes."

Ron says his son now struggles to sit up just a little in bed and when caregivers shower him once a week he sits, exhausted, trying to recover.

Marcel Robert lives in a quiet, darkened room in a rest home. The 31-year-old suffers from a chronic, debilitating illness. Photo / Supplied

"He's continued to worsen regarding sensitivity to light and sound, severe muscular pain and temperature changes similar to ongoing flu."

On ME Awareness Day in May, Robert posted on the ME Awareness Facebook page about his life with the chronic illness and his hope that research will find answers.

"Research for ME is drastically underfunded and there is zero funding in New Zealand," he wrote.

"CBT [cognitive behaviour therapy] and Graded Exercise Therapy are recommended to sufferers despite massive flaws in studies supporting their effectiveness and a key symptom of ME being a worsening of symptoms after exertion.

"Many still see ME as a psychological disorder but there is now overwhelming biomedical research that it's a physical disease."

Robert's hope is that governments, particularly in New Zealand, will support ME research with funding.

At the University of Otago, Professor Warren Tate and a small team of researchers are tackling ME head on.

Robert became part of the research last year and what was discovered gave Ron newfound hope his son might one day recover, even just a little.

He and other ME sufferers look to have malfunctioning mitochondria.

Simply put, mitochondria takes in nutrients from a cell, breaks it down, and turns it into energy.

Tate's research suggested people with ME have mitochondria that have less spare capacity for energy production when under stress.

"We've produced a model to try and explain all of the symptoms of the illness and some of the characteristics, like why don't people get better like a normal viral illness," Tate says.

The team is looking at molecular changes occurring in the blood cells of people with ME.

"There's another code within DNA which responds to environment and things that are happening to you and can change in diseases, called the epigenetic code.

"We've looked at 30 million sites across their whole genome, to look for changes in these little chemical tags, and they change the function of the DNA in terms of whether information gets out or not.

Marcel Robert during a recovery period in 2009. The Dunedin man was once a lively, sport-loving teenager with lots of friends. Photo / Supplied

"These are quite expensive studies and that's why we need the money, but we've got the data and we've shown there are definite changes between people with ME and the control [group].

"We're looking to see whether during a relapse, does that code change as well or not."

Tate says if he gets his budget for next year the team will study what happens after exercise. But it's a big "if".

"Funding in the New Zealand environment with the way the disease is still regarded is just incredibly difficult.

"It's not regarded as an illness in the same category as something like heart disease or diabetes and yet it affects probably 25,000 people in New Zealand, and they're debilitated right from day one many of them.

"It tends to still get put into the basket of being psychiatric."

Tate's own daughter developed ME at age 14. Now 43, she lives with the illness.

Since 2013 Tate has given a session each year to medical students in Dunedin on ME. There is otherwise no formal training.

"With my daughter's permission I talk about her illness and the difficulties our family had with interacting with the medical system, which is still a major issue for people with ME."

Tate says with both he and his wife health professionals he thought they were highly capable of advocating for their daughter.

"But the knowledge of ME and treatment within the medical system was completely ill-equipped.

"People were saying 'Your daughter just doesn't want to go to school. She's just seeking attention'.

"My daughter loved school. She had a great network of friends. You feel so isolated as a family."

University of Otago researcher Professor Warren Tate needs funding to continue his team's research in myalgic encephalomyelitis /chronic fatigue syndrome [ME/CFS]. Photo / Supplied

Tate's research has been able to continue thanks to donations, including tens of thousands from Ron.

In total, Tate, who has been at the university 52 years, is overseeing five ME studies but says without $120,000 in funding the team will be unable to continue next year.

"Sometimes on a Friday you never quite know whether you're going to have enough money to keep your people together by the next week."

An online page Tate set up initially attracted $20,000 in the first month but the donations have slowed to a trickle.

"I'm street fighting. We're scrabbling around at the moment for money. I've applied for quite a few grants over the past five years and never been successful in the mainstream."

ME Awareness NZ says research funding into ME in New Zealand is "woefully inadequate" given the high prevalence and the level of disability it causes.

"About a quarter of people affected are too ill to leave their homes and some are too ill to leave their beds," spokeswoman Rose Camp says.

"It is not okay that many decades after the Tapanui Flu epidemics of the 1980s there still are no diagnostic tests and not even a single drug or treatment specifically approved for ME.

"As a result people with ME, some of whom have been ill since the Tapanui Flu epidemics, are being denied even a basic quality of life. Research is the key to remedying this."

The rest home where Marcel Robert lives. The 31-year-old cannot care for himself because of myalgic encephalomyelitis [ME]. Photo / Google Maps

She says a small number of New Zealand researchers were engaged in ME research and making an impact internationally but their access to funding was severely limited.

"Australia recently announced AU$3 million for biomedical research into ME. There is an urgent need for a similar contestable grant fund in NZ.

"The estimated 20,000 New Zealanders with ME, including 3000 young people and children, deserve nothing less."

For Robert, his lonely existence continues. He is surviving, but not living.

Ron says the research findings boosted his son's confidence in himself.

"The biggest difficulty for Marcel is that since he was 21 he's faced total ignorance of doctors to accept it is a physical disease.

"They were sceptical and essentially called him psychosomatic, prescribing him anti-depressants en masse.

"His friends deserted him largely thinking he was lazy and putting it on to get benefit."

And though Tate and his team represent a glimmer of hope, the light is fading.

"Trouble now is that his small dark world is heading to two years and even TV is difficult," Ron says.

"Every movement is painful and I can only touch him very gently.

"This year's findings will soon be released by the Otago research team and Marcel is clinging onto a thread of hope."

![University of Otago researcher Professor Warren Tate needs funding to continue his team's research in myalgic encephalomyelitis /chronic fatigue syndrome [ME/CFS]. Photo / Supplied](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5cae6a189b8fe8174438d696/1572864239255-CI5R24QZ7JIN4VL5NUQC/Prof+Tate.jpg)

![The rest home where Marcel Robert lives. The 31-year-old cannot care for himself because of myalgic encephalomyelitis [ME]. Photo / Google Maps](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5cae6a189b8fe8174438d696/1572864351434-FFVT08IGKD5MDNKYQ4YA/Oxfort+Court+Rest+Home.jpg)