myalgic encephalomyelitis

ALSO KNOWN AS CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME (CFS), TAPANUI FLU, OR ME/CFS

What is ME?

ME is a debilitating, chronic, multi-system disease that affects the neurological, immune, endocrine, and energy metabolism systems. It most commonly occurs post-infection in both outbreak and sporadic patterns but non-infectious triggers are also possible.

It does not discriminate - affecting all ages, genders, ethnicities and socio-economic groups, leaving the majority (75%) unable to maintain employment. ME is also the most common cause of long-term school absence.

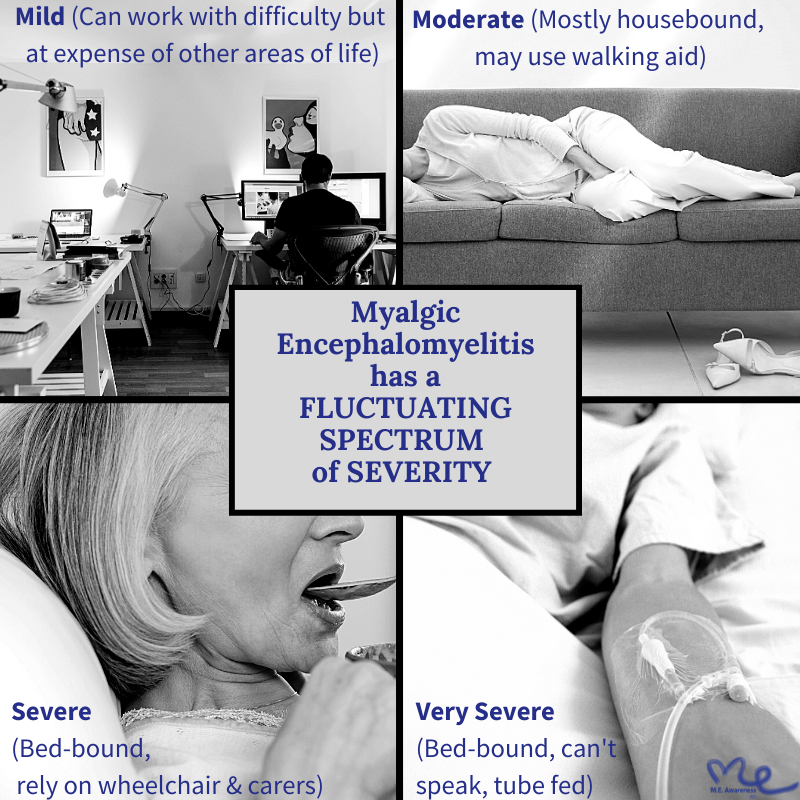

There is a fluctuating spectrum of symptom severity from ‘mild’ (just able to manage work but at the expense of other areas of life) to ‘very severe’ (bed-bound, tube fed, paralysed, without speech). Even ‘mild’ cases can involve the loss of at least 50% of normal function.

A note about NZ outbreaks of ME

There were about three ME epidemics from 1978-1988 in New Zealand. The Tapanui Flu epidemic was the only one ever commonly referred to, which is why many have assumed only the small rural town of Tapanui was affected. In fact, there were hotspots nationwide, with cases numbering in the thousands. Very little research was able to be completed because, despite some very promising preliminary findings, NZ funding authorities repeatedly refused to approve the research grants needed to study these outbreaks in depth.

Stigma and ME

ME/CFS is one of the most misunderstood, misdiagnosed and stigmatized diseases of our time.

ME is neither new nor rare, it has just been invisible. Despite the fact that there have always been those dedicated few, both here and abroad, who have sought to serve people with ME effectively, as a disease it has still largely been victim to decades of systemic injustice, discrimination and neglect from medical institutions, science institutions, and governments world-wide.

Click here to see our short summary “How a name can make millions disappear” that attempts to explain how ME came to be so invisible.

Click here to read a NZ research abstract from Dr Don Baken & colleagues from Massey University on this topic. Click here for a related Massey article.

Symptoms

The hallmark symptom and cardinal feature of ME is ‘post-exertional malaise’ (PEM), which is a delayed (24-48 hrs) significant reduction in functioning and extreme worsening of all symptoms for days, weeks, months or even years after minimal physical or cognitive activity.

‘Minimal’ meaning compared to the individual’s pre-illness ability.

What is considered ‘minimal’ will vary for the individual from one time to another and will vary from one individual to another.

For many patients even minimal exertions like having a conversation or a shower or walking to the mailbox can cause PEM.

See our clinicians guide to PEM here and our explanation for people with ME here.

Common symptoms and comorbidities include:

NB Symptoms can fluctuate in severity from hour to hour, day to day.

The symptom profile can also differ from person to person. It is possible that there are in fact multiple ME subtypes - further research will clarify this.

Onset

The vast majority of ME cases report being triggered by an acute infection. Common viral triggers include Herpesviruses (Epstein-Barr, cytomegalovirus, HHV-6, HHV-7), influenza, and Enteroviral infections such as Coxsackie B.

Less common triggers include non-infectious immune provocations , such as anaesthetics; physical trauma (surgery, concussion or car accident); and chemical exposure.

Around 25% of people have a gradual onset with no obvious trigger.

Genetics plays a role. Individuals with first-degree relatives with ME were found to be 2x more likely to develop the disease.

Geneticists believe the epidemiological pattern of the development of ME is an indication of a common genetic mutation. Within the next 10 years, many people reading this will themselves develop ME or have someone they love develop it. The level of public awareness, medical education and research funding will largely determine the quality of life that loved one will experience.

Pathophysiology

Researchers do not yet comprehensively understand the pathophysiology of ME.

This is largely due to biomedical research into ME being significantly underfunded for decades. See this image for a quick illustration of this.

Despite this, those few dedicated researchers in the field have begun to identify multiple pieces of the complex puzzle that is ME. Objective evidence of underlying abnormalities in the nervous system (neuroinflammation), immune system and cardiovascular system have been identified, as well as abnormalities in red blood cells, muscle, microbiome and, metabolic function. As mentioned, genetic links are also slowly coming clear.

See here for a quick summary of some of the latest research:

Epidemiology

ME is not a rare disease, only rarely diagnosed. There are an estimated 20 million cases worldwide.

NZ prevalence data has not yet been collected. Overseas data based on a relatively tight ME/CFS criteria have quoted a range of prevalence rates from 0.11% to 0.42%, meaning between 5,000 and 20,000 people could be affected in New Zealand. However newer data from the USA, based on actual insurance claims for ME and CFS, has suggested a 0.859% prevalence rate – which could mean there are more than 40,000 people with ME/CFS in New Zealand.

By comparison the established prevalence rate for Multiple Sclerosis in New Zealand is 0.0724% (roughly 3,400 people). ME/CFS could therefore be anywhere between 1.5 and 12 times more common than Multiple Sclerosis. Research has found that (as mentioned in above quote), on average, people with ME are more functionally disabled than people with MS.

ME does not discriminate. All ages, genders, ethnicities and socio-economic groups are affected.

However, it appears to be more common in women (60-65%) than men (30-35%). ME also appears to be less common in those in minority populations and low socio-economic groups, however this is likely due to lack of awareness and access to health care facilities and thus diagnosis.

Quality of Life

A 2015 study by Falk Hvidberg et al. found that the EQ-5D-3L-based Health Related Quality of Life of ME/CFS is significantly lower than the population mean and the lowest of all the compared conditions. HRQOL for ME/CFS was rated as 0.47, general population 0.85, Breast cancer 0.75, Depression 0.62 and Multiple Sclerosis at 0.67, as shown in Figure 3 of the research article.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is a challenge, and can only be done through the discussion of symptoms and by excluding other illnesses that may present in a similar way.

Most standard blood tests will show results in the normal range. While recent research has identified a range of biomarkers and metabolic abnormalities that show that people with ME do have a physical illness, no tests for diagnosing ME are available yet.

Over the last few decades there has been significant inconsistency around the symptoms that are required for a diagnosis of ME.

These are the three most common diagnostic criteria for ME case-definitions:

IOM Criteria (2015) for ME/CFS-SEID.

NB These criteria are very broad but are useful as first screen in a clinical setting)

(The Institute of Medicine/IOM is now known as the National Academy of Medicine.)Canadian Consensus Criteria (2003) for ME/CFS.

It is important to note that those with ME only form a small percentage of those presenting to their GP with ‘chronic fatigue’ .

It is also important to note that both misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis are issues.

The majority of people with ME remain undiagnosed, “An estimated 84 to 91% of people with ME/ CFS have not yet been diagnosed, meaning the true prevalence of ME/CFS is unknown.” (IOM, 2015).

Due to the diagnosis of ME not being made, many people are commonly misdiagnosed, most often with a depressive illness or anxiety disorder.

Others are given the diagnosis of ME or CFS without proper investigative work to rule out other conditions that have different treatment pathways e.g. people may have MS (Multiple Sclerosis), Cancers, MCAS (Mast Cell Activation Syndrome), or Dysautonomias but these diagnoses are often missed.

Go to Resources for further in-depth information on diagnosis and management including a list of Primers.

Management

There are no established treatment options for ME; no treatment centers and not one medication that is licensed for use in the management of ME in New Zealand.

However, there are a range of interventions and strategies for managing some of the symptoms that can lead to degrees of improvement.

In particular, doctors can address sleep problems and pain, as well as common co-morbid conditions.

Common co-morbid conditions

These need to be identified and managed, as doing so can significantly decrease the level of disability.

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)

(see here for resources)

NB The Nasa Lean Test is a very simple screen for orthostatic symptoms, and POTS in particular.Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS)

(see here for MCAS treatment options),Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

Chronic infections

Fibromyalgia

Autoimmune conditions (Thyroid, Celiacs, SLE/Lupus)

Primary sleep disorders (e.g. Obstructive Sleep Apnea or OSA)

Allergies and chemical/food intolerances (IgE/IgG)

Hypermobility, Ehler-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) and ME, as well as Craniocervical instability (CCI), appear to be linked to Severe forms of ME. Overseas there have been cases of ME with CCI, that have gone into remission after surgical correction with an occipital-cervical fusion.

Secondary or reactive anxiety and depression are not uncommon, due to the debilitating nature of ME, coupled with the significant stigma, misunderstandings, and lack of medical and social supports that people with ME experience. Identifying and supportively managing these illnesses is vital. The Clinical Guidelines for Psychiatrists by Eleanor Stein is a great resource for clinicians who are seeking to understand the distinctions between ME/CFS and psychiatric disorders.

CBT, GET and the PACE Trial 2011

Clinical guidelines have often recommended cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET). These treatments were based on a series of studies, and in particular, a large study called the PACE trial (UK, 2011).

The idea behind these treatments was the erroneous belief that people with ME were sick because they had become anxious about the harm that their symptoms were causing them (developed illness beliefs) and had therefore stopped engaging in things that were ‘good for them’, such as exercise. This ideology was interpreted using a cognitive behavioural model formulation based on the fear-avoidance-deconditioning hypothesis. The aim of treatment therefore was to address these ‘anxious beliefs’ and gradually increase activity on the assumption that doing so would lead to recovery by helping the individual to appreciate that pain and fatigue are not harmful, and to regain fitness.

The PACE trial has since been exposed and discredited due to serious methodological flaws, and these therapies (CBT and GET) are now deemed inappropriate and harmful for people with ME. Unfortunately, not before they were included in textbooks, medical school curricula, and treatment guidelines worldwide, including here in New Zealand.

NB That is not to suggest that all therapy or exercise is harmful - what was harmful and remains harmful, is the ideology that drove studies such as the PACE trial.

We are supportive of the need for people with ME to be given supportive CBT, which may be offered to anyone with any other chronic disease.

We also encourage people with ME to be as active as is possible WITHOUT TRIGGERING AN INCREASE IN SYMPTOMS. Research into the physiology of exercise in ME has now shown that people with ME are accurately interpreting their symptoms and that exceeding the window of tolerance for activity results in the unique and defining feature of ME; post exertional malaise (PEM).

Mildly affected patients may tolerate some gentle exercise. More severely affected patients, however, struggle with even simple activities of daily living (eating, showering, brushing teeth, getting dressed) and won't be able to engage in any additional exercise at all. Any exertion that leads to an increase in symptoms should be avoided as much as possible.

Pacing and other self-management strategies

For the majority, pacing proves to be the one and only strategy that seems to offer some benefit. In essence, pacing requires patients to closely monitor and determine how much physical, mental and emotional capacity they have available for each day. Spending more energy than they have in their ‘energy budget’ can result in PEM. Many people report that their symptoms lessen and their quality of life improves when they learn to not overspend their energy budget.

Finding things that they value, to spend what little energy they have on, is important for wellbeing.

There are different metaphors to help with this: Energy budgeting, energy banking, spoon theory, energy envelope. Click here for a guide to pacing by Emerge Australia. We have a number of guides for PEM and pacing - refer to the list on our Resources page.

Other issues to consider

People with ME need support for accessing WINZ benefits (supported living payment and disability allowance) as well as other disability services (disability carpark permits, mobility aids, occupational therapy equipment). For those who are able to work/study, they need support as they will likely need to make work/study modifications to enable them to continue.

Children and young people with ME need particular support around their education. Here is a list of some information.

Carers of people with ME need support. Click here for information.

Local/regional support groups are a great source of help and information.

Prognosis

Prognosis is poor, with less than 5% expected to fully recover. Many improve, but plateau below pre-illness functionality, and with a lifelong relapse-remission pattern. A subset progressively worsen. Regarding recovery, no reliable factors have been identified. Some feel they have ‘recovered’ but in reality have just normalized to their level of function and learnt to manage their illness more effectively.

References

Dimmock ME, Mirin AA, Jason LA (2016) Estimating the disease burden of ME/CFS in the United States and its relation to research funding. J Med Therap 1.

Geraghty, K., Jason, L., Sunnquist, M., Tuller, D., Blease, C., & Adeniji, C. (2019). The 'cognitive behavioural model' of chronic fatigue syndrome: Critique of a flawed model. Health psychology open, 6(1), 2055102919838907.

Gluckman, S.J. (2018). Clinical features and diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. In A.L Komaroff & J Mitty (Eds.), UpToDate.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). (2015). Beyond myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Redefining an illness. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

ME Action. Diagnosis and Management of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis,

ME Action. GET and CBT are not safe for ME – a summary of survey results.

Steincamp, J. (1988). Overload : Beating M.E. : the chronic fatigue and immune dysfunction syndrome. Whatamongo Bay, Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand: Brick Row Publishing/Cape Catley. (p.172)

Valdez A, Hancock E, Adebayo S, Kiernicki D, Proskauer D, Attewell J, et al. (2019) Estimating prevalence, demographics, and costs of ME/CFS using large scale medical claims data and machine learning. Front. Pediatric. 6:412.

Wilshire, CE, Kindlon, T, Courtney, R. (2018b) Rethinking the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome-a reanalysis and evaluation of findings from a recent major trial of graded exercise and CBT. BMC Psychology 6(1): 6.